Study of soil contamination at Wasa and Aboa stations

Aboa station. The generator building (left) and the main building (right). The station area is partly snow-covered even during the summer season. Photo: Anne Swartling

As part of an environmental program, a soil study was initiated by the Swedish Polar Research Secretariat at the Swedish research station Wasa in 1999/2000 and extended to include the nearby Finnish research station Aboa during the season 2001/02. This investigation was initiated to comply with the intentions of the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty concerning monitoring of negative environmental impact from ongoing activities in Antarctica. The purpose of the assessment was to monitor any contamination of soil that could be related to the activities that occur at the research stations during normal conditions.

Background

The Antarctic Treaty was formed in 1959 by twelve states, including the seven states that have territorial demands on Antarctica and a further five states with interests in the area. Today forty states have joined the treaty. As long as the treaty is valid no state has sovereignty in any part of Antarctica. The treaty states that Antarctica is not to be used for military purposes and forbids atomic detonations and radioactive waste. (Jacobsson, 1992). Thanks to the treaty, Antarctica is designated for scientific research, and since the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty was added in 1991, Antarctica is to be seen as a “natural reserve, devoted to peace and science” (Protocol, 1991). The Environmental Protocol prevents mineral exploitation and specifically outlines rules for waste handling and monitoring of environmental impact. Both Sweden and Finland are parties to the Antarctic Treaty and have signed the Environmental Protocol.

Wasa and Aboa stations

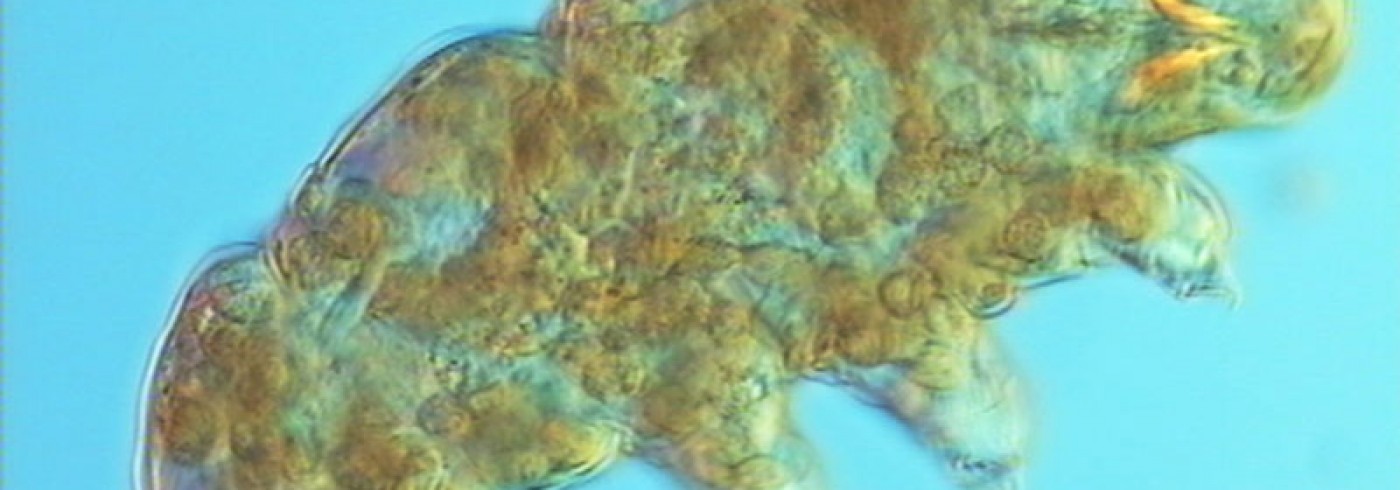

Both stations were built in 1988 on relatively snow-free ground only two hundred metres apart at the Nordenskiöld Base (73°03’S and 13°25’W) at the mountain Basen. This area is part of the mountain range Vestfjella in Dronning Maud Land. The climate is continental at a distance of one hundred kilometres from the sea and about two thousand kilometres from the South Pole. Only one to two percent of the vast continent consists of snow-free ground, and this is the habitat for most of its unique and sparse flora and fauna. The ground is considered to be especially sensitive to environmental disturbance since growth and rate of soil processes is low. At Basen the flora consists of various lichens and mosses, and the micro fauna consists mainly of nematodes, tardigrades and rotifers. Three bird species, namely snow petrel, south polar skua and Wilson’s storm petrel nest at Basen (Thor, 1992).

The stations have been used for research groups of about ten to twenty people during the summer seasons. The Wasa station is built on flat ground and has a main building of 120 m² housing twelve people. There are also two unheated buildings used for storage, the diesel generator and workshops. Two mobile modules are at present used for laboratory work. The yard measures 140 x 60 metres of basalt rock and regolith ground (Larsson, 1989) that is predominantly snow-free during summer season. When the surface layer thaws in the strong sun it is possible to take soil samples without drilling. The Aboa station is of similar size, but its buildings are spread out over a somewhat larger, partly snow-covered area. Aboa station also includes a garage and a helicopter hangar. Waste handling, fuel storage, fuelling, heating, transportation, construction work, waste incineration and grey water discharge are all activities that could cause environmental impact. Most research activities have taken place outside the station areas and have been evaluated to have low environmental impact. The emphasis in the research projects has been on glaciology and geology. No major spills have been reported outside the station areas.

Anne storing samples in a metal box in the glacier rift that was used as a freezer. Temperature was constant at –12˚C. Photo: Warren Papworth.

Sampling and equipment

The first step of this study was to assess what kinds of materials, fuels and chemicals had been used at the stations. The second step was to ascertain where these hazardous materials were used at the stations. This information was gathered by interviewing people with good knowledge of the stations and by studying pictures and reading previous reports. Since the stations are relatively new and operations are well documented much useful information was found. This is the first study of soil contamination from human activities at Basen.

The first samples were collected in 1999/00 at three different locations at Wasa where contamination was likely to be found, such as at the fuel storage site, under the diesel generator building and by the battery storage area under the main building. These samples were brought back to Sweden and checked for a large number of metals, fuel components and excess nutrients. Based on these results a larger sampling was planned.

An exposed sampling pit. Samples were generally taken down to 0.3 metres where the permafrost layer starts. Photo: Anne Swartling

Over a hundred samples were collected at Wasa and Aboa during the 2001/02 expedition. During this expedition, weight of research materials was limited to fifty kilograms per person and special plastic bags were used to collect samples, instead of heavier glass jars, due to weight restrictions on the aircraft. A crowbar and a spade were used to dig larger pits when possible and steel trowels or plastic spoons were used to collect samples. Samples were collected at different levels down to 0.3 metres, where the permafrost layer began. A handheld drill was used as a backup to get samples when the ground was frozen (photo 4).

At Wasa samples were taken both at hot spots where there would be a larger risk of contamination, as well as evenly spread out over the entire yard. The area was divided into squares of 20 x 20 metres and one random sample was retrieved from each square. The outer limits of the square grid were measured using a theodolite. The outer lines passed through two known GPS points to facilitate a repetitive sampling process in the future. All sampling spots were photographed and their respective GPS positions were documented.

At Aboa samples were collected only at sites where there was a high probability of contamination. Greywater samples were also collected from the greywater outlet. Three reference samples were collected on the north top part of Basen, where the station activities could not influence the ground. Since a freezer was not available, these samples were kept in a glacier rift that held a constant temperature of –12°C until transported back to the laboratory in Sweden for analysis.

Warren Papworth using a drill to retrieve a sample from the frozen ground under the generator house where a diesel spill had occurred. Photo: Anne Swartling

Results

The random sampling of the entire yard at Wasa station did not reveal any unknown sites of contamination.

The sampling at hot spots shows that there is a certain environmental impact on the soil, which originates from fuel leaks, but that this is limited to small, defined areas within two to three metres and is concentrated to the surface layer.

At Wasa station the samples showing the highest amounts of fuel residues were at the helicopter landing site, the former and present fuel storage sites and under the diesel generator building. The highest amount of “oil” (total aliphatic hydrocarbons) was 4 000 parts per million. These observations are comparable to other sites where spills have occurred in Antarctica. (Deprez, 1999, Gore, 1999 and Krzyszowska, 1990). Other than the most volatile compounds it is likely that these spills will remain since it has been shown that fuel spills in these environments are persistent over time (Gore, 1999).

At Aboa station fuel residues were found mainly in four spots. Two were located at the fuel storage site, one outside the garage (where fuel had been stored) and one at the helicopter hangar. In addition an increase in sulphur was found at the site downwind of the generator building, which is probably caused by burning diesel containing sulphur.

The soil samples were also analysed for content of heavy metals such as lead, which could be a component of fuel. An increase in lead was found in a few samples, with a maximum value of 31 ppm as compared to normal lead levels in this area (reference site) of 11 ppm. An accumulation of lead has also been observed at other stations as a result of human activity, for instance at Scott Base, where it was suggested that lead was not particularly mobile in these soils (Sheppard, 2000). No increase in nutrients was observed in any soil samples.

Dates

November 2001–February 2002

Participants

Project leader

Anne Swartling

DNV Certification AB

Stockholm, Sweden

References

Jacobsson, M. 1992. Antarktis: om sydpolens historik, juridik och politik. Utrikesdepartementet informerar 1992:1, Stockholm.

Protocol on the Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty. 1991.

Thor, G. 1992. Biological investigation in Vestfjella and Heimefrontfjella. In: Swedish Antarctic research programme 1991/92. A cruise report. Swedish Polar Research Secretariat, Stockholm, 54–57.

Larsson, K. 1989. The Wasa Station – environmental aspects. In: Swedish Antarctic Research Programme 1988/89. A cruise report. Swedish Polar Research Secretariat, Sweden, 39–41.

Deprez, P.P., Arens, T., Locher, H. 1999. Identification and assessment of contaminated sites at Casey Station, Wilkes Land, Antarctica. Polar Record 35 (195), 299–316,

Gore, D.B. Revill, A.T. Guille, D. 1999. Petroleum Hydrocarbons ten years after spillage at a helipad in Bunger.Hills, East Antarctica. Antarctic science 11 (4), 427–429.

Krzyszowska, A. 1990. The content of fuel oil soil and effect of sewage on water nearby the H. Arctowski Polish Antarctic Station (King George Island). Polskie Archiwum Hydrobiolgii 37 (3), 313–326.

Sheppard, D.S., Claridge G.G.C., Campbell, I.B. 2000. Metal contamination of soils at Scott Base, Antarctica. Applied Geochemistry 15, 513–530.